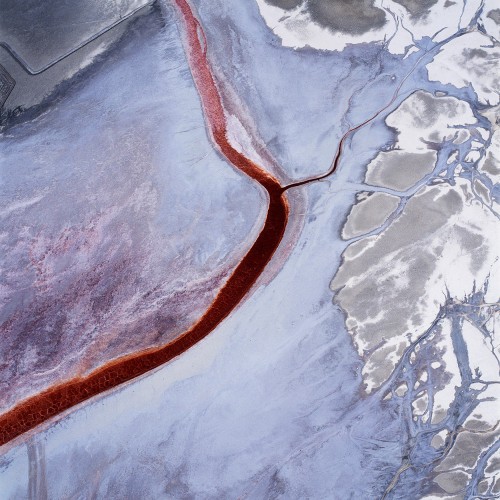

Archival Pigment Print | 48 by 48 inches, edition of 5 + 2AP | 29 by 29 inches, edition of 10 + 2AP

By Diana Gaston

Reprinted from Aperture, Volume 172

The ground is bleeding. A red river cuts a path through a bleached valley, winding toward a lake that is no longer there. Seen from the air, the river and its dry terminus appear otherworldly.In actuality, this terrain is located in Owens Valley, an arid stretch of land in southeastern California, between the Sierra Mountains and the White-Inyo Range. The history of this region is the stuff of California legend: a story of engineers, politicians, and big land owners working together to divert water to the rapidly growing desert city of Los Angeles, generating a thriving agricultural industry and an environmental disaster in the process. Beginning in 1913, the now infamous Los Angeles reclamation project effectively diverted water from Owens Valley to the Los Angeles Aqueduct, providing a substantial amount of the city’s water supply.i By 1926, the lower Owens River and Owens Lake were essentially depleted of water, leaving a vast exposed salt flat with unusually concentrated mineral levels and extremely vulnerable topsoil.ii The situation has been exacerbated by fierce winds that sweep through the valley and dislodge carcinogenic particles from the lakebed, creating a pervasive dust cloud known as the Keeler fog (named for the town on the east side of the lake). The Owens Lake region, the largest source of particulate matter pollution in the United States, is now undergoing an EPA approved, state implemented plan to control the spread of this hazardous matter.iii After decades of accelerated destruction, the ground is once again flooded, this time by EPA officials in an effort to diminish the toxic dust that settles in the soil, vegetation, and lungs of nearby inhabitants. From the air, high above this damaged wasteland, the ground assembles itself into something spectacular and horrifying. This is what David Maisel sees through his camera, a contemporary version of the sublime.

It was the unusual pink glow of the lakebed that caught David Maisel’s attention when he drove through Owens Valley on a return trip to the San Francisco Bay Area.iv He had passed through this corridor before, but at that point, in the summer of 2001, he began to ask questions about the lake and its history. For the past twenty years his photographic work has focused on areas of environmental destruction—strip mining, cyanide leaching fields, abandoned tailings ponds, clear-cut logging, firestorms—and this valley struck him as a significant site for exploration. The Lake Project, as the Owens Lake pictures have come to be known, is part of a larger, ongoing series loosely titled Black Maps. The early thinking for this series actually began during his undergraduate work at Princeton, when he accompanied his photography professor Emmet Gowin on flights over Mount Saint Helens and the heavily logged forests of the Pacific Northwest. The experience of that aerial view, and the realization that the overwhelming destruction of the logging industry was essentially on par with the damage brought about by a volcanic eruption, established his future direction as a photographer. In the work produced in subsequent years, he brings a quiet urgency to his pictures, framing the complexities of an environmentally impacted landscape with equal measures of documentation, metaphor, beauty and despair. He continues to photograph from an aerial perspective, the elevation enabling him to read the landscape like a vast map of its undoing.

The view of Owens Valley from above is at once terrifying and exalted. These are precisely the contradictions that Maisel pursues in his work, seeking out vast reaches of land that might be further transformed by the abstraction of the camera and the disorienting perspective of the plane. The elevation serves as a compositional device, enabling him to either fill the frame with the tumultuous pattern of the ground by flying very low, or to glean a broad view of the valley from a higher elevation. His perspective is constantly shifting as the ground rises or falls away, and the images register a sense of his suspension and dread; the horizon lies somewhere beyond the frame of these photographs, and the viewer is rendered directionless. Maisel is assembling a map from numerous vantage points, piecing together the complex overlay of human intervention, natural systems, and the inherent chaos and logic that inform them both. In considering this particular landscape, a space violently inscribed by the demands of a desert population, the interdependent systems of the natural world and the physical body are made unusually apparent. From the air, the landscape emerges as a dynamic biological structure; even in its depleted state, the river and its tributaries adhere to the desert floor like nerve endings, veins, or arteries; the mottled red river bank suggests magnified cellular patterns, a coagulated pool of blood, an inferno; a colony of invasive marks presumably created by potash mining are clustered like boils on the desert floor; vehicles traversing back and forth across the lakebed cut frenzied pathways through newly planted grasses, revealing a kind of madness; elsewhere, the geometric order of gleaming copper pools, convey a sinister logic in the mining industry establishing itself on the dry lakebed to harvest minerals laid bare by the evaporated water.

This photographic treatment of landscape as metaphor does not provide a great deal of specificity, or a detailed understanding of the environmental problems at hand. Nor do his numbered titles offer any information beyond a rigorous cataloguing system of his own making. As engaged as he is in the surrounding issues, Maisel is not attempting to make literal records of environmental destruction. Rather, he seeks a distance that scrambles a conventional reading of the landscape. In this altered state, the laws of gravity are undone, solid ground gives way, and the photograph is experienced as a transcendent vision or tone poem, as much as a map of ecological disaster. He uses this highly charged method of seeing to reveal the landscape in something other than purely visual terms, translating it as an archetypal space of destruction and ruin that mirrors the darkest corners of our consciousness.

Maisel has photographed Owens Valley extensively on two separate occasions—in September 2001 and in June 2002. In the intervening months the EPA began its work to stabilize the area, utterly transforming the region yet again. From the air, a new map emerges, as a grim order is imposed on the land. The environmental control measures, introduced to help dampen the toxic dust on the lakebed, call for shallow flooding, managed vegetation of salt grasses, and gravel cover. With each succeeding layer of intervention the landscape becomes more and more complex, as previous scars are covered over, irrigation pools expand into an authoritative grid system, and the colors on the ground are artificially buffered. It is an unsettling thing to witness the acceleration of geologic time, to trace the destruction and alteration of a region’s topography in the space of a few generations. The camera is particularly adept at momentarily arresting these shifts, maintaining a visual archive of the landscape’s transformation. Maisel’s images offer brief measures of time, suspending elements of grace within a continuum of failure and erasure.

________________________

i For a thorough history of the Owens Valley-Los Angeles water reclamation program, see Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water, Viking, New York, 1986.

ii The situation was worsened in the 1970s, when the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power drew additional water to feed a second aqueduct by sinking groundwater wells on land the city owns in Owens Valley, further depleting the valley water table and area springs. See Steve Hymon, “Owens Valley Deal in Jeopardy,” Los Angeles Times, August 25, 2002, for a concise history of the ongoing fight for water.

iii The dust from the lakebed contains carcinogens such as nickel, cadmium, arsenic, as well as sodium, chlorine, iron, calcium, potassium, sulfur, aluminum, and magnesium. The EPA plan is supposed to be fully executed by 2003, with the option to implement additional controls if necessary to meet the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) by 2006. For more information, see US Environmental Protection Agency, Owens Valley Particulate Matter Plan, posted September 29, 1999, http://www.epa.gov/region09/air/owens/fact.html. At this writing, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (DWP) and Inyo County, which includes Owens Valley, is in dispute over delays to the state-required environmental analysis of the river restoration plan. The agreement, signed in 1997, called for returning water to the Owens River, enabling it to flow again by 2003. See Hymon, “Owens Valley Deal in Jeopardy.”

iv The concentration of minerals in what little water remains in the lakebed is so artificially high, that annual blooms of microscopic bacterial organisms are common, resulting in the water turning pink, and sometimes a deep red.