By Geoff Manaugh

Reprinted from Library of Dust, Chronicle, 2008

In Haruki Murakami’s novel Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, an unnamed man finds himself walking through an unnamed town. Its depopulated spaces are framed most prominently by a Clock Tower, a Gate, and an Old Bridge. The man is told almost immediately to visit the town’s central Library—an unspectacular building that “might be a grain warehouse” for all its allure. “What is one meant to feel here?” the man asks himself, crossing a great, empty Plaza. “All is adrift in a vague sense of loss.”

Once inside the Library, the man meets a Librarian. The two of them sit down together, and the man then prepares to read dreams. They are not fairy tales written with pen and ink, however, but the psychic residues of long-dead creatures, a gossamer field of electrical energy left behind in the creatures’ bleached skulls. Weathered almost beyond recognition, one such skull is “dry and brittle, as if it had lain in the sun for years.” The skull has been transformed by time into something utterly unlike itself, marked by processes its former inhabitant could not possibly have anticipated.

Each skull is the most minimal of structures, seemingly incapable of bearing the emotions it stores hidden within. One skull in particular “is unnaturally light,” we read, “with almost no material presence. Nor does it offer any image of the species that had breathed within. It is stripped of flesh, warmth, memory.” It is at once organic and mineralogical, living and dead.

The skull is also silent, but this silence “does not reside on the surface, [it] is held like smoke within. It is unfathom-able, eternal”—intangible. One might also add invisible. This “smoke” is the imprint of whatever creature once thought and dreamed inside the skull; the skull is an urn, or canister, a portable tomb for the life it once gave shape to.

The Librarian assists our unnamed narrator by wiping off a thin layer of dust, and the man’s dream-reading soon begins.

•••

Dust is a peculiar substance. Less a material in its own right, with its own characteristics or color, dust is a condition. It is the “result of the divisibility of matter,” Joseph Amato states in his book Dust: A History of the Small and the Invisible. Dust is a potpourri of ingredients, varied to the point of indefinability. Dust includes “dead insect parts, flakes of human skin, shreds of fabric, and other unpleasing materials,” Amato writes.

Many humans are allergic to dust and spend vast amounts of time and money attempting to rid their homes and possessions of it, yet dust’s everyday conquest of the world’s surfaces never ends. Undefended, a room can quickly be buried in it.

Dust lies, of course, at the very edge of human visibility: it is as small as the unaided eye can see. And dust is not strictly terrestrial. “Amorphous,” Amato continues, “dust is found within all things, solid, liquid, or vaporous. With the atmosphere, it forms the envelope that mediates the earth’s interaction with the universe.” But dust is found, too, beyond the earthly sphere, in the abiotic vacuum of interstellar space, a freezing void of irradiated particles, where all dust is the ghostly residue of unspooled stars, astronomical structures reduced to mist.

Strangely representational, the chemistry of this stardust can be analyzed for even the vaguest traces of unknown components; these results, in turn, are a gauge for whatever elemental hells of radiation once glowed when the universe burned with intensities beyond imagining. Those astral pressures left chemical marks, marks that can be found on dust.

Such dust—vague, unspectacular, bleached and weathered by a billion years of drifting—can be read for its astronomical histories.

Dust, in this way, is a library.

•••

A geological history of photography remains unwritten. There are, of course, entire libraries full of books about chemistry and its relationship to the photographic process, but what the word chemistry fails to make clear is that most of these photographic chemicals have a geological origin: they are formed by, in, and because of the earth’s surface.

Resists, stops, acids, metals, fixes—silver-coated copper plates, say, scorched by controlled exposures of light—produce images. This is then called photography. Importantly, such deliberate metallurgical burns do not have to represent anything. Photography in its purest, most geological sense is an abstract process, a chemical weather-ing that potentially never ends. All metal surfaces transformed by the world, in other words, have a literally photographic quality to them. Those transformations may not be controlled, contained, or domesticated, but the result is one and the same.

Photography, in this view, is a base condition of matter.

•••

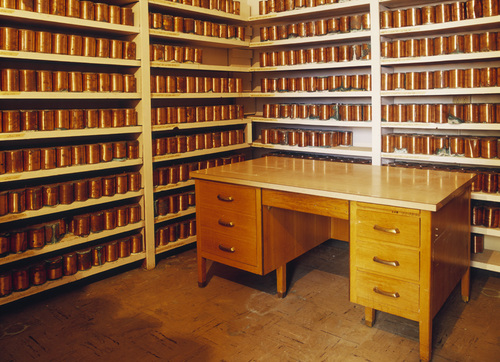

David Maisel’s photographs of nearly 110 funereal copper canisters are a mineralogical delight. Bearded with a frost of subsidiary elements, their surfaces are now layered, phosphorescent, transformed. Unsettled archipelagos of mineral growths bloom like tumors from the sides and bottoms—but is that metal one sees, or some species of fungus? The very nature of these canisters becomes suspect. One is almost reluctantly aware that these colors and stains could be organic—mold, lichen, some yeasty discharge—with all the horror such leaking putrescence would entail. Indeed, the canisters have reacted with the human ashes held within.

Each canister holds the remains of a human being, of course; each canister holds a corpse—reduced to dust, certainly, burnt to handfuls of ash, sharing that cindered condition with much of the star-bleached universe, but still cadaverous, still human. What strange chemistries we see emerging here between man and metal. Because these were people; they had identities and family histories long before they became unnamed patients encased in metal, catalytic.

In some ways, these canisters serve a double betrayal: a man or woman left alone, in a labyrinth of medication, prey to surveillance and other inhospitable indignities, only then to be wed with metal, robbed of form, fused to a lattice of unliving minerals—anonymous. Do we see in Maisel’s images then—as if staring into unlabeled graves, monolithic and metallized, stacked on shelves in a closet—the tragic howl of reduction to nothingness, people who once loved, and were loved, annihilated?

After all, these ash-filled urns were photographed only because they remain unclaimed; they’ve been excluded from family plots and narratives. A viewer of these images might even be seeing the fate of an unknown relative, eclipsed, denied—treated like so much dust, eventually vanishing into the shells that held them.

It is not a library at all—but a room full of souls no one wanted.

•••

Yet perhaps there is something more triumphant at work here, something glorious, even blessed. There is a profoundly emotional aspect of these objects, a physical statement that we, too, will alter, meld with the dust and metal: an efflorescence. This, then, is our family narrative, one not of loss but of reunion.

There is a broader kinship being proclaimed, a more important reclamation occurring: the depths of matter will accept us back. We will be rewelcomed out of living isolation. We are part of these elements, made of the dust that forms structures in space.

Maisel’s photographs therefore capture scenes of fundamental reassurance. The mineralized future of everything now living is our end. Even entombed by metal, foaming in the darkness with uncontrolled growths—there is splendor.

•••

To disappear into this metallurgical abyss of reactions—photographic, molecular—isn’t a tragedy, or even cause for alarm. There should be no mourning. Indeed, Maisel’s work reveals an abstract gallery of the worlds we can become. Planetary, framed against the black void of Maisel’s temporary studio, the remnant energies of the long dead have become color, miracles of alteration. These are not graves, the photographs proclaim: only sites of transformation.

That is our final, inhuman release.

•••

At the end of winter 2005, David Maisel traveled to a small city in Oregon. There were bridges, plazas, and gates. He was there to locate an old psychiatric hospital—a building now housing violent criminals—because the hospital held something that interested him.

Upon arrival, he met with the head of security, who already knew why Maisel had come. The two of them walked down a nearby corridor, where Maisel was shown what he’d been looking for. It was an isolated room behind a locked door—smaller, less official, than expected.

Within it was the Library of Dust.