by David Maisel

1.

We consulted our atlas and named it, saw the pinpricks on the page meant to indicate its barren surface. What prolonged cataclysm, what continuous collapsing, could yield a display of iridescent color across miles of valley floor?

We sought to find a pilot, so that we could peer beyond the rim of the expanse, to map the scarred interior. This one is prone to crashes, we were told, and besides, his door was locked, his office dark. Then, there is a man who can help you, and the first flight began, the plane sputtering, the pilot silent.

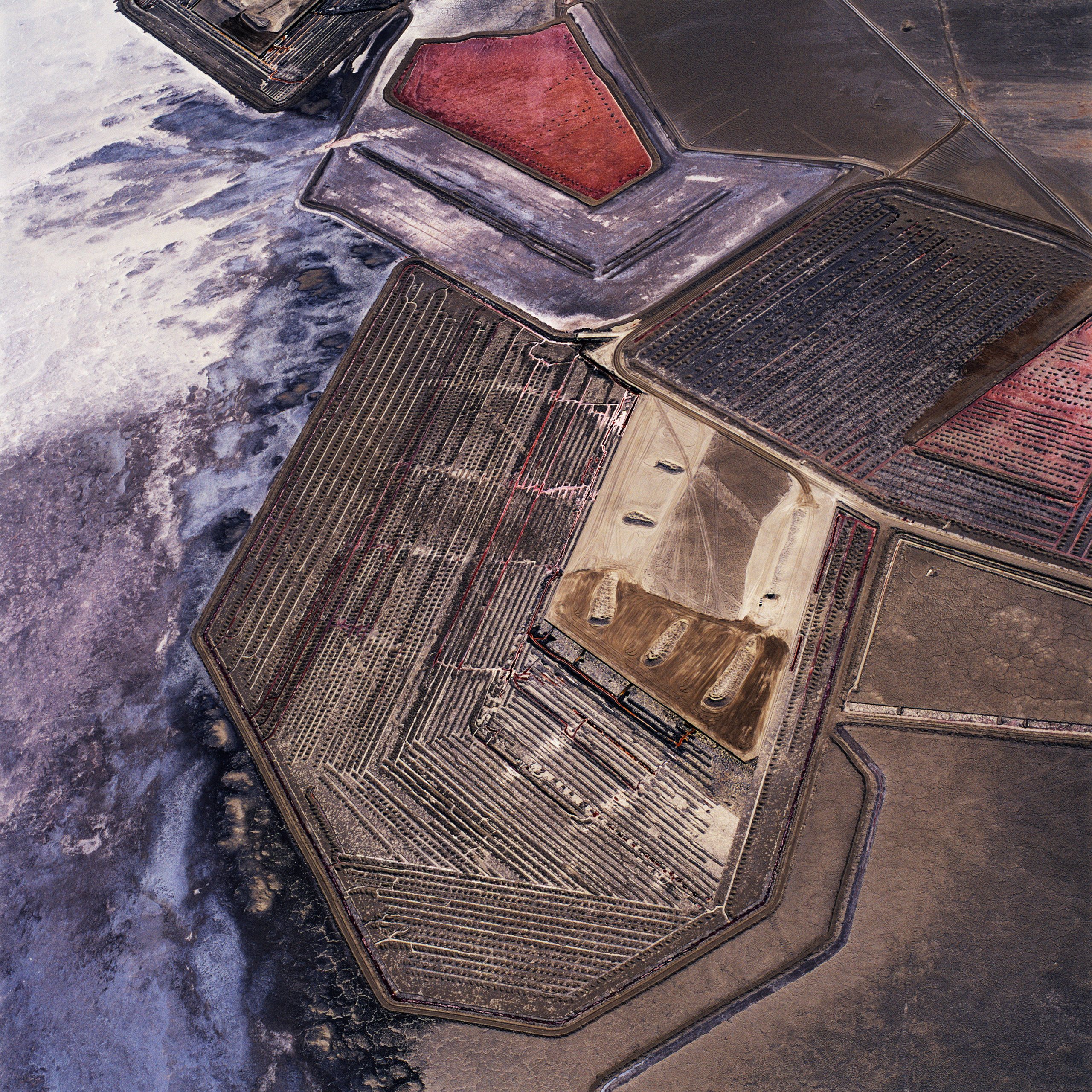

Rising above the site, we became a disembodied eye—camera lens trained on the dead lake, its skin peeled back, the exquisite corpse revealed. A river of blood, a split-tongued vein, a hundred acres dried like a scab, pigmented dust mottled, a galaxy’s map splayed out beneath us.

Inhuman, human, inhuman.

The smear of green at the periphery seemed obscene, hinting at the chance for vestigial life. Is resurrection possible? Moving toward the south, the planes of poison arranged themselves into a prismatic structure, an enormous diode, a microchip, an enemy encampment, its gridded streets dotted with tent cities or funeral pyres, the mind of the torturer displayed.

Red, pink, coral, rose, pearl, graphite, opal. The seduction of surfaces. The dizzying collapse of one system into another. We gathered images in a vain effort to comprehend. Toward the east: the fantastic synapse, the vast neuron firing blanks. We expose our film and map our inability to know.

We move in lower. The frame fills with blood-red saline fields. We are within the lake’s body now; it will subsume us. The river coalesces with crystalline forms. If death is the mother of beauty, as the poet Wallace Stevens said, then these images may serve as the lake’s autopsy.

2.

Midway through this flight (between the fifth and sixth frames of the twenty-seventh roll of film), we determine from our position within the steeply banking plane relative to the darkening red river, that it was Hass, wasn’t it, who wrote that death is the mother of beauty, though it was Stevens who spoke of the palm at the end of the mind, and it was Ashberry who told of Francesco Parmigianino’s self-portrait in a convex mirror, how the artist held the mirrored globe away from himself and sketched the warped reflection he saw in the glass

(though, had the globe been clear and not silvered, it would have acted like a lens, and cast the artist’s image upside down, and the semblance of his surroundings upside down, too), even as the room he was drawing, and his position within it, pulled away from him in the curvature of the mirror; and his rendering set the scene down somehow whole, though transformed into a fictive space, and it was laid like a transparent skin, like a film, a projection of itself, upon the film-thin sheet of paper; even as Ashberry, speaking directly to Francesco, writes that Your eyes proclaim that everything is surface. The surface is what’s there / And nothing can exist except what’s there;

and as our film registers the lakebed’s light onto its surface, Stevens observes that his lapidary, shimmering palm stands on the edge of space, which is located, it seems, where we are now suspended, circling above what lies below, the netherworld of the lake; and we are lured into this numinous space, where imagination and reality divide, only to reflect each other; and the cumulative effect is that of an enormous act of doubling, through mirrors held up to each other, like Smithson’s mirrors strewn across fields of gravel, where all is reflected onto itself, and thereby erased; and the plane moves forward, and the film spools ahead.

3.

What forms do we inscribe in the air as we arc above the lake? What pattern, what logic might be revealed in a transcription of our movements onto the lake’s surface? Or perhaps it is the other way round; the lake rendering itself onto us as we picture it through our lenses. We pivot and spin.

Next flight: We approach from the north, at an altitude that allows us to see the whole of the vast gray city being wrested from the lakebed’s surface. The altimeter reads seventy-five hundred feet. With the window flung open we contort ourselves, leaning toward the bleak, malevolent civilization taking form below, that pulls us toward it with a force like gravity. The freezing air rushes in; we are too high. Cannot breathe. Lungs hammering, in need of oxygen, we descend.

The city rises toward us, filling the frame, writhing. An ash-colored miasma of cul-de-sacs and tumors, bisected with an avenue or a landing strip. One system is a cancer of randomness, the other an annihilating regimen of precision. Lines and swirls and pattern-making, markings and delineations, cancellations and erasures. We are told that the city’s construction is a flood zone, made to resuscitate the lake. To us it seemed a lost civilization being formed, an archaeology in reverse. Poseidon, Atlantis. My daughter had asked, Is this the lake with the monster living in it? It seemed it was.

At the southern shore, faintly pocked zones reveal attempts to grow salt grass in the wasteland. To feed what creature? The only moving things are the dust devils that coalesce and spin in the afternoon heat, swirling white towers of cadmium, arsenic, sulfur, iron, calcium, nickel, potassium, aluminum, chlorine. The lakebed emits three hundred thousand tons of such matter every year; thirty tons of it arsenic, nine tons of it cadmium.

We had dreamed of building cities, fields of glittering towers, urban fantasies meant to house our hopes of progress; now we seek out dismantled landscapes, abandoned, collapsing on themselves. Rather than creating the next utopia, we uncover the vestiges of failed attempts, the evidence of obliteration.

Our photographs are a torrent of fragments meant to indicate the whole. Imagine the film, and time itself, spiraling backward until water reappears in the lake bed. At first a faint trickle, then a river, pouring in from the aqueduct at the southern edge, decades of drainage reversed in a moment. The shoreline advances over the wasteland; the fish are spawning; and from the skeletal remains of the town of Keeler a skiff is being launched from a neighborhood pier, as towheaded kids swim under the gaze of their parents.

Our own gaze upon this scene cannot be sustained. It is a fiction, and it vanishes. What is left, for certain, is the City of Ash, the Artificial Flood Zone, the Potash Mine, the Plains of Toxic Dust. Much as we long to breathe life back into this corpse, resurrection is beyond our grasp.

4.

If this is what we are permitted to view, then what remains concealed? What has been edited? We cannot absorb what we are seeing as we see it; we are pure reflex, exposing film as the forms shift beneath us. Then is it intuition that forms the basis of this report? And is it a desire for clarity, or for obfuscation, that brings you this finite selection? Stitching together these fragmentary images doesn’t tell the story of this lake anymore than an autopsy tells the life the deceased once lived. Though the facts lie here before us in these tableaux, we are inventing a fiction, and as we thread our way through it, we are drawn deeper and deeper into a maze from which escape is impossible.

Our spiraling path spells out forms against the sky, reflected back in the dead, emptied lake. We make a vortex of circular arguments, elliptical paths, elegant and circuitous. Can we synthesize the information before us? Can you decode it for me?

To autopsy means to see for oneself. The facts of the lake’s destruction are irrefutable and more potent than any our imaginations can provide. The lake is real; its history is that of its ruin by human intervention. The eradication has yielded a stately magnificence, and this seems a terrible contradiction: beauty borne of environmental degradation.

The conundrum is thus: demise of the lake = dizzying, imperial beauty. And further: We are seduced by it; its beauty obscures everything else about itself. It is the only part of itself it will allow us to know. And what kind of pictures, with what sort of compelling ambiguities, should we make to mark the lake’s disappearance?

5.

The lake as a sacred text in a language we cannot decipher. The lake as emblem of the unknowable; the lake as a project that yields only more questions. The lake as loss; the photographs as mourning, an elegy for a lost landscape. The lake as enigma. The lake as limitless, sensuous apparition. The photographs as the lake intensified.

The futility of this endeavor isn’t lost on us, our vain attempts to steer a clear path, to state our position, to lay out the facts. We insisted on clarity and the cartographer’s dispassion, the vivisectionist’s art. The photographs were to be empirical reason made visual. We find ourselves instead to be awash in contradiction, seduced by the sublime surfaces of this desecrated place.

Ochre, rust, oxblood, jade, sage, sienna. At a lower elevation now, the air in the plane begins to heat, and we strain against our confines. We can almost give in to the languor of the engine’s drone; the motor-drive of the camera winds more slowly, the focal shutter closing its blackness on the scene like a heavy lid. The camera blinks, the lake blinks back, and we are gone.